"The Worst Plague Since the Black Death"

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Just after the end of the First World War, Annie Huble fell ill while she was alone at the Huble family’s Giscome Portage homestead with her six young children. In the bitter cold of winter, Annie was too sick to fetch the firewood or milk the cows. The dire situation took a turn for the better when Pete Pierroy, a First Nations man who had performed work for the Huble family in the past, stopped by to check in on them. Finding them in a sorry state, he stayed with the family, ensuring that the house was heated and that they had enough to eat until Annie was on the mend. While this story has a happy ending, many others who came down with the flu in 1918 were not so lucky.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was a global disaster. The so-called “Spanish Flu” first struck in the spring of 1918, and by the time it ended in 1920, had killed between 30,000 and 50,000 Canadians. In the months following the First World War, it is estimated that the flu infected around 500 million people and killed approximately 50 million worldwide. Though it is commonly called the Spanish Flu, the virus did not originate in Spain. In fact, even today, it is not clear where it did originate, but the first known case was reported at a military base in Kansas on March 11, 1918, and from there, it was able to spread very quickly with the movements of soldiers, both during military engagements overseas and when they returned to their home countries. Read on to learn how the Spanish Flu and its aftermath affected millions of people around the world, and the ways it impacted society right here at home.

What's in a Name?

Due to its nickname in North America and Europe, many people believe that the 1918 Influenza originated in Spain, but this is not the case. During the First World War, Spain remained neutral. While nations that were actively engaged in the conflict suppressed news of the flu to keep up morale, Spain was the only country in which the media could fully report on the illness and its effects. When the flu made headlines in May 1918, most accounts were from Spanish news sources, which led many people to assume that the pandemic began in Spain. Official sources today refer to this H1N1 outbreak as the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, but many still know it as the Spanish Flu.

A public announcement published in the

Prince George Citizen on October 18, 1918.

Symptoms and Pathology

In the spring of 1918, the first wave of the epidemic raised few alarms. Though there seemed to be more widespread and serious cases of flu, the war was still everyone’s main focus, and due in part to a lack of reporting on the sickness by countries involved in the conflict, many wrote off the higher than usual infection and mortality rate as just a particularly bad flu season. By September, however, the virus had mutated into a vicious illness that could kill its host within 24 hours of showing symptoms. Spread of the virus was difficult to contain, as patients first developed regular flu-like symptoms that did not cause immediate concern. With mild symptoms, those infected with the disease continued to go about their business, all the while spreading the virus to people with whom they came into contact. As their illnesses progressed, many of the afflicted developed pneumonia or other severe complications, with some ultimately dying of infections or lack of oxygen in the blood. Lasting roughly from September to November of 1918, this second wave of the flu claimed more victims than all of the other waves combined. Two subsequent waves of the virus occurred in the spring of 1919 and the winter of 1920, but neither were as severe or as widespread as the 1918 fall outbreak.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada (PA-025025)

There was no cure for the Spanish Flu and no preventative vaccine. At the time, it was widely believed that the flu was caused by bacteria, but even if medical professionals had identified it as a virus, antivirals did not yet exist. Prevention was the best treatment for the flu, and many Canadian cities implemented measures to slow its spread. Public meetings were prohibited, schools were closed, flu masks in public became mandatory, and commercial business hours were reduced. Due to the highly infectious nature of the disease, coupled with non-compliance with many of the preventative measures, the contagion continued to spread. Unscrupulous entrepreneurs took advantage of people’s fears by marketing their products as essential to preventing or treating the virus.

Many people turned to patent medicines made with alcohol or narcotics, which claimed to relieve pain and treat symptoms. Others attempted to manage flu symptoms independently by using substances such as heroin for coughing and insomnia, alkaline medicines to treat acidosis (excessive acid in the body), and Epsom salts to clean out the digestive tract. None were particularly effective, and as we know today, many had the potential to cause more harm than good.

While seasonal flus tend to kill individuals with compromised immune systems such as the very young and the very old, the 1918 influenza pandemic claimed the lives of more young people between the ages of 20 and 40 than any other demographic. This was not only due to the symptoms brought on by the flu, but to the body’s attempts to fight off the disease. In the body of a young adult with a strong immune system, the infection triggered an overproduction of immune cells known as a “cytokine storm.” This massive immune reaction centered in the lungs, causing inflammation and fluid build-up which resulted in severe respiratory distress and in many cases, death. Combined with the war’s effect of concentrating young people together in crowded and unhygienic conditions, death rates among this demographic were unusually high. The loss of tens of thousands of young adults to influenza compounded the impact of the 60,000 Canadians that were killed during the First World War.

Social Impacts

The 1918 influenza broke out at a turbulent time. The Great War had been raging for four years and many countries had lost huge numbers of young men and women to the war effort. The pandemic exacerbated stress on a system that was already missing a significant portion of their working class. Medical facilities and staff alike were underequipped and overworked, resulting in volunteers with little training being called upon to help organize infirmaries in schools, hotels, and other public buildings. As the flu rampaged throughout Canada, children were orphaned, families lost their primary wage earners, and businesses were forced to shut their doors due to lost profits. During its peak, undertakers and gravediggers could not keep up with the work as hearses and coffins fell into short supply. In some places, funerals were limited to 15 minute gatherings; in others, bodies were buried in mass graves without ceremony. Reports surfaced of people trapped indoors with the bodies of dead family members because they were too sick themselves to report the deaths. Contemporary writers made comparisons to the Black Death, the plague that ravaged Europe and Asia during the 14th century. For many, the possibility that a sickness could kill so many, so quickly, was hard to comprehend in their modern era.

The Millar Addition high school was used as a hospital during the pandemic.

Courtesy of The Exploration Place (P981.35.69)

First Nations Communities

While all British Columbians were affected by the 1918 pandemic in one way or another, First Nations communities were particularly hard hit. Official sources report between 670 and 1,139 deaths amongst First Nations communities, though it’s likely that flu deaths were underreported. On the coast, the sickness hit right as canneries were gearing down for the season. Infected workers brought the illness with them when they returned to their villages and reserves. Many reserves were in poor condition with inadequate water supplies, housing, and sanitation systems. Most reserves did not have enough room to grow crops or keep livestock, and traditional subsistence patterns had shifted to depend on the changing economy of the province. As services began to shut down across the province, reserves were often unable to obtain the supplies they needed to care for their ill members. A lack of physicians in general, combined with the predominantly racist views of the settler population meant that there were few who were willing to travel to reserves to tend to First Nations people. Those who wanted to use European medication were often denied the opportunity, and many others turned to traditional medicines to treat symptoms instead. Additionally, the flu tended to exacerbate existing conditions such as tuberculosis which had previously gone untreated in First Nations populations for many of the same reasons. In the Prince George region, one third of the population at Saik'uz (Stoney Creek) perished, and the majority of people at Khast'anlhughel (Reserve No. 2, at Shelley) and Lhezbawnichek (Reserve No. 3, at Miworth) fell ill, with many deaths.

The social implications of the 1918 Influenza in First Nations communities were even more profound than those felt in society as a whole. Increasing birth rates and high death rates among the Indigenous people of the province meant that the population in 1918 was quite young. As the flu typically attacked young adults, this undoubtedly contributed to the higher volume of deaths among First Nations, though the lack of care and assistance provided to these communities during the pandemic should not be understated. First Nations families lost parents, children, and elders, and with them, the living knowledge, traditions, and histories of their cultures.

Close to Home

In British Columbia, the flu arrived in Vancouver and Victoria by early October, and quickly spread along interior rail lines and up the coast on steamships. When it reached Prince George later that month it spread quickly, prompting an immediate response. Influenza is scarcely mentioned in the Prince George Citizen in the early weeks of October 1918; any references speak of efforts to contain the disease in the eastern provinces. On October 18, just three days after the newspaper claimed that there were no reported cases in the city, the Citizen announced that public gatherings in the city had been banned following the emergence of 22 cases of influenza. The same edition noted the symptoms of the disease and outlined the steps that individuals should take if they found themselves ill. Local recommendations included many that we would expect to see today, but also a few that were undoubtedly products of their time. These included keeping the body warm, keeping living spaces between 65 and 72°F (18-22 °C), eating plain, nourishing food, avoiding alcohol, and keeping one’s feet warm and dry. Among other things, the paper recommended staying away from other people as a preventative measure and especially if flu symptoms developed.

Dr. Edwin Lyon (right) served as the medical health officer for the city during the flu pandemic.

Courtesy of The Exploration Place (P981.19.29)

BC Provincial Police Inspector T.W.S. Parsons worked alongside Dr. Lazier caring for flu patients and arranging temporary provincial hospitals.

Courtesy of The Exploration Place (P982.52.16)

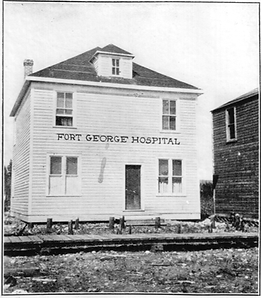

The situation in Prince George remained fluid, as newspapers reported one day that the influenza epidemic was on the decline, and reported the next day that the situation showed little sign of improvement. As in many other cities across the country, a call was put out for volunteer nurses to help relieve the strain on professionals. The city hospital was not prepared to take on so many cases so temporary hospitals were set up at the Connaught Hotel, Union rooming house, and the Millar Addition high school. Many patients were treated in their homes due to a lack of available accommodation. The hospitals were supervised by Dr. Edwin Lyon, medical health officer for the city, and Dr. David Lazier, medical health officer for the Fort George district. As cases in the city continued to rise, the need for medical equipment increased, and calls were put out for people to drop off thermometers at the temporary hospitals. In his diary, Al Huble notes that his business partner Ed Seebach was sick with the flu in Prince George on November 5. Huble also notes that he himself was sick with the flu on November 10th and 11th. He was working in the partners’ store when Seebach returned to Giscome Portage on November 12th.

Richard Corless Funeral Ledger

Courtesy of the Northern BC Archives & Special Collections (2007.23)

During the pandemic, deceased victims were sent to Richard Corless’s funeral home at the corner of Quebec and Fourth Ave. Between 1916 and 1931, Corless kept a ledger recording all of the funerals that he performed. When paired with the Prince George Citizen newspaper database, the ledger helps to provide a record of pandemic deaths in the city. In total, the ledger lists 55 deaths due to pneumonia, the top flu-related cause of death, between October 1918 and April 1919, when no new cases were reported in the city. The ledger contains records of deaths from Prince George and the surrounding area, including First Nations reserves. Some deaths occurred in outside communities, and were brought into the city for burial, while others had arrived from outside destinations for treatment.

A great deal of fear was expressed for pre-emptors and trappers who worked away from civilization for long periods of time. Searches were conducted for those who had not been heard from for a while, and often the findings were grim. Perhaps this is why Pete Pierroy decided to look in on the Huble family that winter’s day. Huble family oral history records do not specify the date of Annie Huble’s illness, though we know it was between December 1918 and February 1919; during these months Al Huble spent a good deal of time away from the homestead and his wife’s sickness is not recorded in his daily diary. He does record the “children all sick with flu” on March 9th and 10th, 1919. Given this timeline, it is likely that the family contracted a milder version of the flu than the one that had rampaged through Prince George in November, as less severe cases were reported by the Prince George Citizen as early as December 13, 1918 Though it is impossible to know if other pre-emptors at Giscome Portage fell ill, it appears as though they fared at least as well as the Huble family. There were no deaths from the area reported in the Corless funeral ledger.

A Lasting Legacy

The Spanish Flu interrupted life and left gaps in families, communities, and nations that were impossible to fill. Mothers and fathers lost children, husbands lost wives, and children became orphans. Soldiers who had made it through months or years on the front lines perished on home soil, days away from reuniting with their loved ones. Others made it back, only to unwittingly spread the sickness to their families and home communities. In the end, the flu claimed the lived of approximately 4,000 British Columbians.

The 1918 flu pandemic created an opportunity for healthcare officials to learn from the mistakes that had been made during the outbreak. In 1919, the federal government established the Department of Health (now known as Health Canada), a move directly influenced by the pandemic and the shortcomings in the healthcare system that had come to light during the crisis. Today, we have a much better understanding of what causes and spreads the flu, as well as what can be done to prevent and treat it. Still, there is much that we as individuals can learn from the Spanish Flu and other pandemics. Chief among these are whispers from the past that resonate loudly today: stay safe, stay home, and look out for one another.

George and Frank Jorgensen. Both died during the flu pandemic.

Courtesy of The Exploration Place (2003.30.8)

Additional Information

What is a Pandemic?

The term pandemic does not refer to a specific disease, but rather to the way in which a disease spreads. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a pandemic is “an outbreak of a disease that occurs over a wide geographic area and affects an exceptionally high proportion of the population.”

What is Herd Immunity?

Herd immunity helps to protect individuals in our society who are unable to protect themselves against diseases. When people refer to herd immunity, they usually do so in reference to vaccines. The invention and use of vaccines have allowed societies to protect public health by creating herd immunity, and have helped to either eradicate or prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

Imagine there are one hundred people standing in a room. Ninety-nine of these people have been vaccinated against a certain disease, and one person has not. The individual who was not vaccinated is not likely to contract the disease because the people around them have been protected against it. The vaccination of the larger population safeguards those who have not been vaccinated, such as infants, as well as people who are immunocompromised and therefore at greater risk for contracting disease, like people undergoing chemotherapy or individuals with HIV.

Herd immunity can also occur without vaccines, though it can take much longer. When individuals contract a disease, they eventually either recover or pass away. Individuals who recover are typically considered immune to the disease, which means they will not contract it again, and they will not spread it to other people. Luckily, we do not need to wait until 99% of the population is immune to a disease before herd immunity kicks in. The percentage is dependent on how infectious the disease is. A highly infectious disease, such as measles, requires that approximately 90% of the population to be immune from the disease in order to protect the remaining 10%. Using a contemporary example, current estimates suggest that 60% of the population will need to become immune to COVID-19 through vaccination or exposure to the virus in order to see the benefits of herd immunity.

Educational Resources

There are a number of excellent sources for teaching the Spanish Flu to elementary and secondary school students. Here are a couple that we recommend.

This Social Studies based kit focuses on primary and secondary source analysis to learn more about the flu in Prince George. This kit is recommended for secondary school students.

https://libguides.unbc.ca/1918_flu_epidemic/prince_george

Defining Moments offers a number of lesson plans for tackling the Spanish Influenza with primary and secondary school students. Areas of study include Canadian history, science, geography, health and nutrition, Indigenous studies, and more.

https://definingmomentscanada.ca/in-the-classroom/spanish-flu/lesson-plans/